Politics

DEVELOPING: FAA Issues Nationwide Ground Stop for United Airlines Flights at Several Airports Due to ‘Technology Issue’

The Federal Aviation Administration on Wednesday issued a nationwide ground stop for United Airlines flights at several airports due to a ‘technology issue.’

BREAKING: United Airlines has issued a nationwide ground stop and is holding all departures due to a technology issue. pic.twitter.com/HyxD4KqqaO

— Sam Sweeney (@SweeneyABC) August 7, 2025

“The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration said on Wednesday it issued a ground stop for United Airlines (UAL.O), flights at several U.S. airports while the company itself said its teams were working to resolve a tech outage as soon as possible,” Reuters reported.

‘Due to a technology issue, we are holding United mainline flights at their departure airports. We expect additional flight delays this evening as we work through this issue. Safety is our top priority, and we’ll work with our customers to get them to their destinations,’ United Airlines said in a statement to The Daily Mail.

CBS News reported:

There is a ground stop for United Airlines flights at Chicago O’Hare Airport Wednesday evening.

United said in a statement that a “technology issue” is causing them to hold departures.

“We expect additional flight delays this evening as we work through this issue. Safety is our top priority, and we’ll work with our customers to get them to their destinations,” the statement continued.

The technical issues are also impacting airports in Denver, Houston, San Francisco and Newark.

Video taken by a passenger at O’Hare shows a line of United planes stopped on the tarmac that have recently landed, waiting because no gates are available.

DEVELOPING…

The post DEVELOPING: FAA Issues Nationwide Ground Stop for United Airlines Flights at Several Airports Due to ‘Technology Issue’ appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.

Politics

President Trump Taps Dr. Ben Carson for New Role — A HUGE Win for America First Agenda

Dr. Ben Carson is the newest member of the Trump administration.

On Wednesday, former Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Ben Carson, was sworn in as the national adviser for nutrition, health, and housing at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins shared that Carson’s role will be to oversee Trump’s new Big Beautiful Bill law, which aims to ensure Americans’ quality of life, from nutrition to stable housing.

After being sworn in, Carson shared, “Today, too many Americans are suffering from the effects of poor nutrition. Through common-sense policymaking, we have an opportunity to give our most vulnerable families the tools they need to flourish.”

WATCH:

BREAKING Dr. Ben Carson has been sworn in as the National Nutrition Advisor to Make America Healthy Again

THIS IS A HUGE WIN pic.twitter.com/Dr5AsSDkRM

— MAGA Voice (@MAGAVoice) September 24, 2025

Per USDA:

Today, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke L. Rollins announced that Dr. Benjamin S. Carson, Sr., M.D., was sworn in as the National Advisor for Nutrition, Health, and Housing at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

“There is no one more qualified than Dr. Carson to advise on policies that improve Americans’ everyday quality of life, from nutrition to healthcare quality to ensuring families have access to safe and stable housing,” said Secretary Rollins.

“With six in ten Americans living with at least one chronic disease, and rural communities facing unique challenges with respect to adequate housing, Dr. Carson’s insight and experience is critical. Dr. Carson will be crucial to implementing the rural health investment provisions of the One Big Beautiful Bill and advise on America First polices related to nutrition, health, and housing.

“As the U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development in the first Trump Administration, Dr. Carson worked to expand opportunity and strengthen communities, and we are honored to welcome him to the second Trump Administration to help lead our efforts here at USDA to Make America Healthy Again and ensure rural America continues to prosper.”

“Today, too many Americans are suffering from the effects of poor nutrition. Through common-sense policymaking, we have an opportunity to give our most vulnerable families the tools they need to flourish,” said Dr. Ben Carson. “I am honored to work with Secretary Rollins on these important initiatives to help fulfill President Trump’s vision for a healthier, stronger America.”

On Sunday, Dr. Carson was one of the many speakers at the memorial service of the late TPUSA founder Charlie Kirk.

During the memorial service, Carson highlighted that Kirk was shot at 12:24 p.m. and then continued to share the Bible verse John 12:24, which reads, “Verily, verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.”

WATCH:

Ben Carson reads John 12:24 at the Charlie Kirk’s funeral. Charlie was shot at 12:24.

It reads: “Very truly I tell you, unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds”

God is moving and speaking. pic.twitter.com/0ZbVTAwwYl

— Danny Botta (@danny_botta) September 21, 2025

The post President Trump Taps Dr. Ben Carson for New Role — A HUGE Win for America First Agenda appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.

Politics

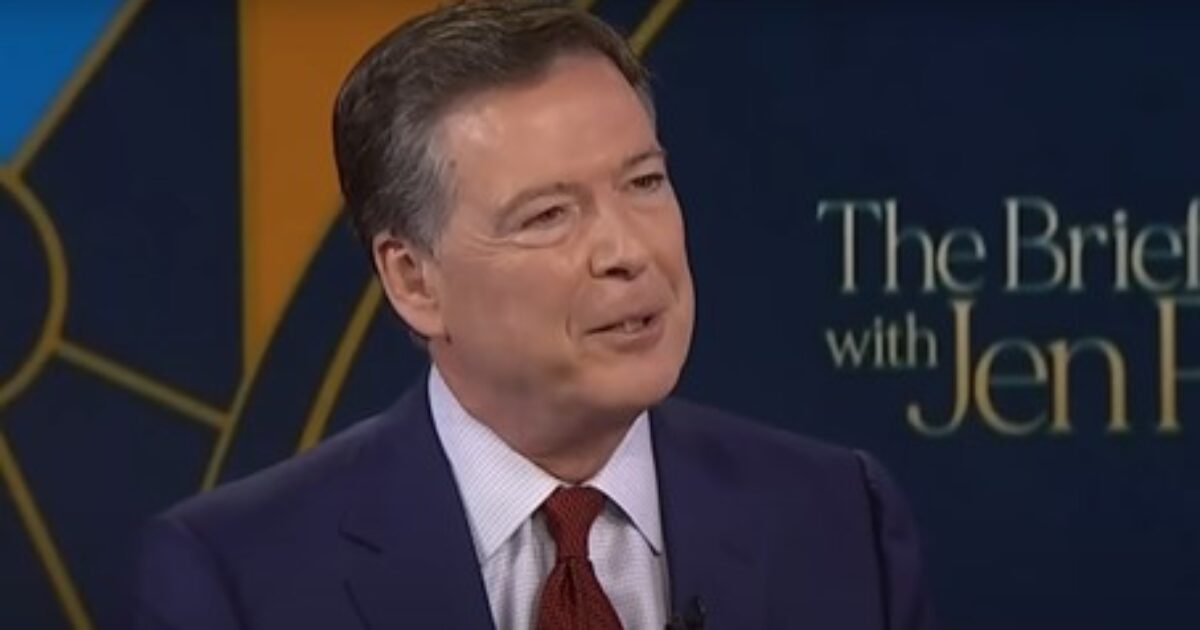

LEAKED MEMO: Deep State Prosecutors in the Eastern District of Virginia Claim There Isn’t Enough Evidence to Convict Comey Amid Reports of Imminent Indictment

On Wednesday evening, disgruntled officials in the Eastern District of Virginia leaked contents of a memo explaining why charges should not be brought against James Comey.

As reported earlier, former FBI Director James Comey is expected to be indicted in the Eastern District of Virginia in the next few days.

Comey will reportedly be charged for lying to Congress in a 2020 testimony about whether he authorized leaks to the media.

Officials in the Eastern District of Virginia are still fighting to stop Comey from being charged after Trump fired US Attorney Erik Siebert.

President Trump last week fired Erik Siebert as the US Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia because he refused to bring charges against Letitia James, Comey, Schiff and others.

On Saturday evening, President Trump announced that he had appointed Lindsey Halligan – his personal attorney who defended him against the Mar-a-Lago raid – as US Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Now, with just days to go before the statute of limitations runs out to charge Comey for lying during a September 30, 2020 testimony, Lindsey Halligan is reportedly gearing up to indict Comey.

Prosecutors reportedly gave newly sworn-in Halligan a memo defending James Comey and explaining why charges should not brought against the fired FBI Director.

Per MSNBC’s Ken Dilanian:

Two sources familiar with the matter tell me prosecutors in the EDVA US attorney‘s office presented newly sworn US attorney Lindsey Halligan with a memo explaining why charges should not be brought against James Comey, because there isn’t enough evidence to establish probable cause a crime was committed, let alone enough to convince a jury to convict him.

Justice Department guidelines say a case should not be brought unless prosecutors believe it’s more likely than not that they can win a conviction beyond a reasonable doubt.

Two sources familiar with the matter tell me prosecutors in the EDVA US attorney‘s office presented newly sworn US attorney Lindsey Halligan with a memo explaining why charges should not be brought against James Comey, because there isn’t enough evidence to establish probable…

— Ken Dilanian (@DilanianMSNBC) September 24, 2025

The post LEAKED MEMO: Deep State Prosecutors in the Eastern District of Virginia Claim There Isn’t Enough Evidence to Convict Comey Amid Reports of Imminent Indictment appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.

Politics

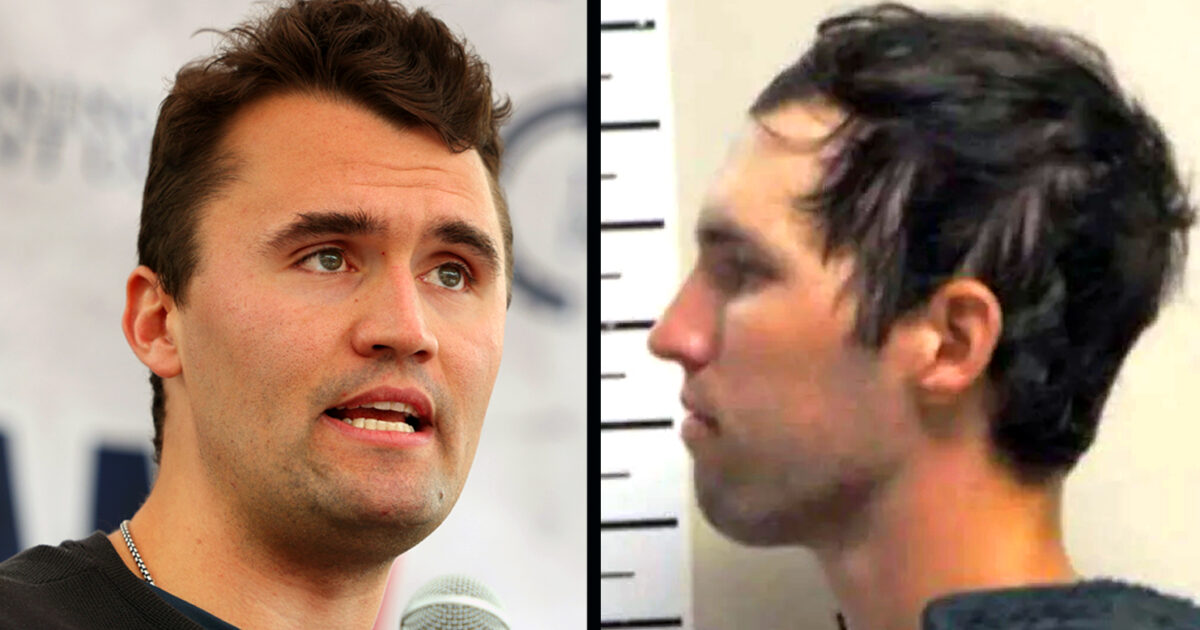

Nearly 8 in 10 Voters Say the United States is in Political Crisis After the Assassination of Charlie Kirk

Nearly eight in ten voters believe that the United States is in a political crisis in the wake of the assassination of conservative icon Charlie Kirk.

According to a Quinnipiac University national poll of registered voters released on Wednesday, a massive 93 percent of Democrats, 84 percent of independents, and 60 percent of Republicans said the nation is in a political crisis.

“The Kirk assassination lays bare raw, bipartisan concerns about where the country is headed,” Quinnipiac University Polling Analyst Tim Malloy said of the poll results.

Quinnipiac reports:

Seventy-one percent of voters think politically motivated violence in the United States today is a very serious problem, 22 percent think it is a somewhat serious problem, 3 percent think it is a not so serious problem, and 1 percent think it is not a problem at all.

This is a jump from Quinnipiac University’s June 26 poll when 54 percent thought politically motivated violence in the United States today was a very serious problem, 37 percent thought it was a somewhat serious problem, 6 percent thought it was a not so serious problem, and 2 percent thought it was not a problem at all.

Nearly 6 in 10 voters (58 percent) think it will not be possible to lower the temperature on political rhetoric and speech in the United States, while 34 percent think it will be possible.

Over half, 54 percent, of voters believe the US will see increased political violence over the next few years. Another 27 percent said they think it will stay “about the same,” while just 14 percent believe it will ease.

A 53 percent majority also said they are “pessimistic about freedom of speech being protected in the United States.”

Surprisingly, a 53 percent majority also believes the current system of democracy is not working.

“From a perceived assault on freedom of speech to the fragility of the democracy, a shudder of concern and pessimism rattles a broad swath of the electorate. Nearly 80 percent of registered voters feel they are witnessing a political crisis, seven in ten say political violence is a very serious problem, and a majority say this discord won’t go away anytime soon,” Malloy added.

The vast majority, 82 percent, said the way that people discuss politics is contributing to the violence.

“When asked if political discourse is contributing to violence, a rare meeting of the minds…Republicans, Democrats, and independents in equal numbers say yes, it is,” Malloy said.

The survey was conducted from September 18 to 21 among 1,276 registered voters with a margin of error of +/- 3.3 percentage points.

The post Nearly 8 in 10 Voters Say the United States is in Political Crisis After the Assassination of Charlie Kirk appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.

-

Entertainment6 months ago

Entertainment6 months agoNew Kid and Family Movies in 2025: Calendar of Release Dates (Updating)

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoBrooklyn Mirage Has Been Quietly Co-Managed by Hedge Fund Manager Axar Capital Amid Reopening Drama

-

Tech6 months ago

The best sexting apps in 2025

-

Entertainment5 months ago

Entertainment5 months agoKid and Family TV Shows in 2025: New Series & Season Premiere Dates (Updating)

-

Tech7 months ago

Tech7 months agoEvery potential TikTok buyer we know about

-

Tech7 months ago

iOS 18.4 developer beta released — heres what you can expect

-

Tech7 months ago

Tech7 months agoAre You an RSSMasher?

-

Politics7 months ago

Politics7 months agoDOGE-ing toward the best Department of Defense ever